Formula 1 power units are the most thermally efficient internal combustion engines ever made—but does that mean they could power your commute?

On paper, Formula 1 engines sound like engineering miracles: over 800 horsepower from just a 1.6-liter V6, and thermal efficiency numbers that exceed 50%, shattering anything seen in the consumer automotive world. So why aren’t we seeing anything like this under the hood of your average road car?

The idea is tempting: shrink the engine, add hybrid components, and use less fuel to go just as fast. But the reality is far more complicated, both technically and economically.

Yes, They’re Efficient—But Only at the Track

First, it’s important to understand what F1 engine efficiency means. These power units are thermally efficient at high loads and full throttle, where most of the energy from combustion is effectively turned into speed. On an F1 track, cars spend 60–75% of a lap at full throttle. This is the ideal zone for these engines.

But your daily commute? Not so much. Road cars operate at partial throttle nearly all the time. In that setting, F1 engines would be wildly inefficient, guzzling fuel just to idle through traffic.

Exotic Materials and Extreme Engineering

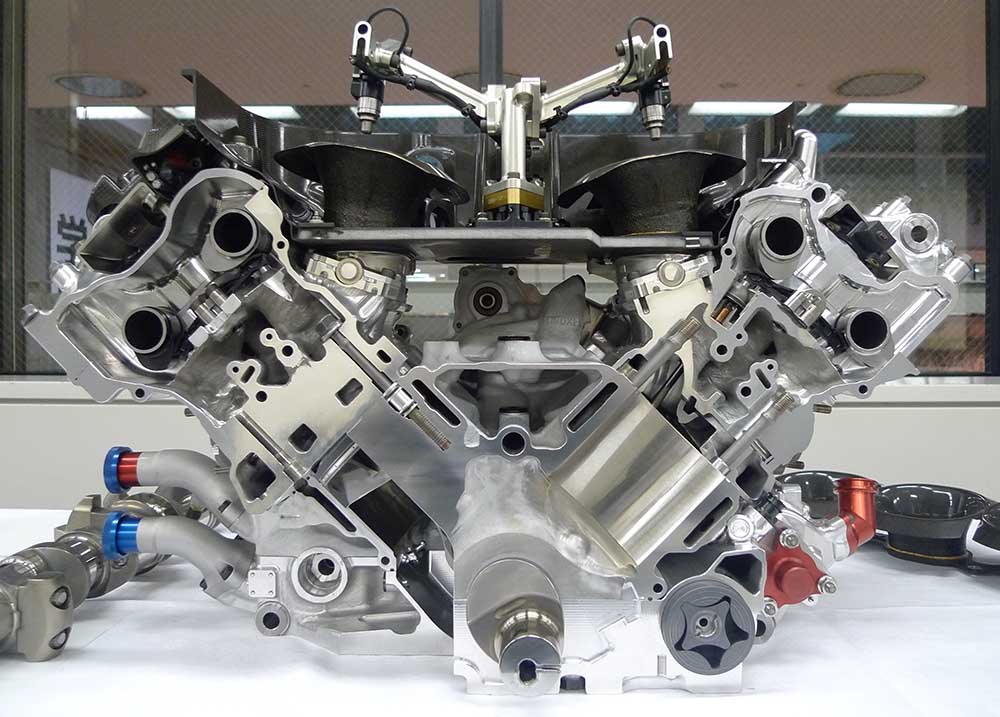

An F1 engine can’t just be dropped into a Honda Civic. These units are built using ultra-lightweight alloys, Inconel-coated components, and carbon fiber systems with tolerance levels so tight that the engine must be preheated before it can even start. The fuel isn’t standard pump gas either—it’s E10 synthetic fuel, specially refined for consistent burn characteristics.

Even if the RPM and output were capped to road-legal levels (say 5,000 RPM and 200 HP), the parts and cooling systems still wouldn’t hold up. These engines are made to survive about 8 race weekends (roughly 6,000 km) before needing a rebuild. Your family sedan? It’s expected to last 200,000+ km with minimal maintenance.

The Mercedes-AMG One: Proof of Concept

Mercedes did try to bring F1 tech to the street with the AMG One hypercar, which features a slightly detuned 2016-spec F1 engine. Even with extreme engineering compromises and sky-high development costs, the AMG One still requires pre-heating, has limited mileage, and costs millions of dollars. It’s a technological marvel, but not remotely practical.

Why It Doesn’t Translate

Here’s a breakdown of why F1 engine tech won’t make it to the road anytime soon:

- Operating Window: F1 engines are efficient at high revs and loads. Road cars live in the opposite conditions.

- Thermal Management: F1 engines require airflow at high speed for cooling. Road cars rely on fans and radiators in traffic.

- Materials & Cost: Exotic materials and tight tolerances make manufacturing prohibitively expensive.

- Longevity: F1 engines are built for performance, not endurance.

- Complexity: Systems like the MGU-H (harvesting turbo heat) are effective at 200 mph, not 30.

The Real Takeaway: Trickledown Tech

While you won’t see an F1 power unit in your next Toyota, the trickle-down effect is real. Hybrid systems, energy recovery, turbocharger tech, and combustion tuning all benefit from F1 R&D. Consumer engines today—like Toyota’s M20A-FXS hybrid engine with 41% thermal efficiency—are already applying F1-learned principles in more practical forms.

The Future? Go Electric (or Efficient at Scale)

If the goal is road car efficiency, scaling electrification or grid-level thermal power is more impactful than chasing hyper-engineered ICEs. Public transport, buses, and shared EV platforms will do more for emissions than ever squeezing a few more MPGs from an exotic combustion engine.

That said, F1 will continue to serve as a fascinating test bed for the limits of performance, efficiency, and sustainability. Just don’t expect your next grocery run to sound like a V6 turbo screaming at 12,000 RPM.